|

by A. I. ASIWAJU (1974)

— « Perturbateur professionnel, escroc (sic), faussaire, déserteur, condamné à diverses reprises par les tribunaux militaires et par les juridictions criminelles et correctionnelles de droit commun de la colonie... »

(The Governor-General of French West Africa, Marc h 1923) 1.

— « Patriote de grande classe, ancien fonctionnaire d'élite, a été toute sa vie, le vivant exemple de l'honnêteté, du dévouement, du courage et du mérite ».

(Government citation in 1964 for the posthumous title of « Grand Officier de l'Ordre National du Dahomey ») 2.

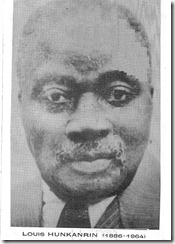

Such were the contradictory evaluations of Louis HUNKANRIN, the Porto-Novian who proved not only a real thorn in the flesh of French administrators of Dahomey but also some kind of suspect to the post-independence political regimes of his country. This was not a peculiar experience in French West Africa where most outstanding opponents of French rule were generally little regarded by their countries' post-independence governments led mostly by pro-French leaders who tended to be indifferent, if not equally antagonistic, to the purpose and method of these critics of the colonial regime. Such were the contradictory evaluations of Louis HUNKANRIN, the Porto-Novian who proved not only a real thorn in the flesh of French administrators of Dahomey but also some kind of suspect to the post-independence political regimes of his country. This was not a peculiar experience in French West Africa where most outstanding opponents of French rule were generally little regarded by their countries' post-independence governments led mostly by pro-French leaders who tended to be indifferent, if not equally antagonistic, to the purpose and method of these critics of the colonial regime.

This political atmosphere indexes certain methodological difficulties attendant on the historian's efforts to evaluate the man. Hunkanrin lived his life mostly as a victim of the French indigénat regime (3) which turned him into a chronic prisoner and detainee. This fact limits the sources from which the investigator could draw his information. Still studied mostly through the jaundiced records of French colonial administrators and jurists who, in most of the cases preferred against him, were at once the plaintiffs and judges, Hunkanrin has remained one of the rare African leaders deplorably little known. His understandably limited private papers, now in the custody of his surviving daughter, are ill-organised and generally inaccessible by reason of the frequent absence of the custodian from Porto-Novo where the material are still kept in a family house. Contemporary newspapers published mostly in Dahomey, Senegal and France, which contained information about Hunkanrin were, though numerous, generally poorly produced and strictly con-trolled, and the complete number of the issues are not yet discovered anywhere (4). Louis Hunkanrin's own greater association with the educated élite, than with the masses, limited knowledge of him to a rather restricted circle of close friends and relations, so that the historian is deprived of the advantage of a systematic collection and evaluation of oral evidence from a larger number of informants (5). But despite these problems, there is at least some room for a. preliminary assessment.

The contention in this paper is that Louis Hunkanrin was neither the crook which the French colons imagined nor the nationalist which he is generally considered today (6). As reflected in his popular cognomen, " Eke l'oju oti" (7), he '.vas simply a strong-willed, indefatigable and rigid adherent to the twin-virtues of fairness and humanity. One of his biographers caught the picture when he observed that 'son amour de la justice et sa profonde sympathie pour les opprimés ont déterminé ses lignes d'action politique" (8). This character was bound to get into trouble with the French colonial authorities, operating the indigénat régime of discrimination between 'subjects' and 'citizens'. But to take him for a Dahomeyan nationalist simply because he spent a better part of his active life in various colonial prisons and detention camps is to miss the fact that what he opposed was administrative abuse, and not French rule as such. An admirer of Blaise Diagne, the number-one 'black-French' politician of Senegal whom he accompanied on a conscription tour of Dahomey in 1918, (9) Louis Hunkanrin was not different from the first generation of educated élite ail over French West Africa wbo, prior to 1958, could not conceive of independence status for their homelands (10). His aspirations were for a Dahomey whose interests were 'indissolublement liés à ceux de la France' (11). The fact that he did not become a Jomo Kenyatta or an Nkrumah for Dahomey and the incredible vacillation of the Dahomeyan Governement which had to wait until he was dead before conferring a national honour on him, ail point to the degree of reservation with which Hunkanrin was regarded even by Dahomeyan s. His commitment to the course of ail led him to embrace communist ideas ; and this, perhaps more than any other consideration, placed. him in permanent suspicion of both the colonial and postcolonial regimes.

continued

|

Les commentaires récents